CONTENT

Regardless of your preparation, you might stray off your path or even get totally lost. Generally, it is best to return the same way to the path or the first trail marker, but in the conditions described above, this is not always easy.

WHEN YOU STRAY OFF THE PATH

- When you realize you are no longer on the right path and are lost, you should first make sure you are safe. If necessary, move away from cliffs and other dangerous areas, put on a helmet, and find suitable terrain where you can assess the situation and plan your next steps. Carefully consider the dangers you might encounter and the tools you have in your backpack.

- Review the terrain using a hiking map and determine the direction you should go next.

- When determining your route, consider the type of terrain (forest, cliffs, grass, etc.), objective hazards, weather, and of course, your experience and knowledge. Important: the shortest route is not necessarily the fastest, let alone the safest!

- Only upon reaching a prominent feature (a road, for example), should you start looking for details. Generally, it’s advisable to go about finding your main goal gradually, step by step (as described below).

If you can’t find a suitable/safe path on difficult terrain (cliffs, steep wet grass, caves), if you don’t have the proper equipment (rope, harness, helmet), or if continuing would be extremely dangerous for any other reason, do not hesitate calling for help. Call mountain rescue at 112! They might be able to assist you with advice and guide you to safety over the phone. In extreme cases, they'll find you and safely escort you to the valley.

- At night, illuminated objects appear closer than they really are.

- In fog, we hear better because sound reflects off water droplets.

- It’s harder to notice changes in terrain (gradient, changes in direction).

- Distances seem longer.

- At night, you must account for a delay in vision focus when looking from a lit map to the surroundings.

- In darkness, we can see better using “peripheral vision”. An object you’re directly focused on may be less visible than if you shift your gaze slightly away.

- At night in narrow valleys, you can see only a small part of the sky, which is why you might not see all the stars or you may misidentify the most recognizable constellations.

- Paths and roads intersect at acute angles towards settlements.

- In Slovenia, northern slopes are generally less vegetated and steeper, the tree line is lower than on southern slopes, and snow lasts longer. Pastures are usually located in southern slopes.

- Knowing the direction of local winds can help roughly determine the cardinal directions. You can also observe the orientation of plant growth in exposed places.

- At night and especially in cloudy weather, you can notice the reflection of lights from large cities.

- Traffic noise carries quite far, even more so at night and on quiet days (weekends, holidays).

Basic orientation equipment should always be in your backpack, even for the shortest trips: hiking map, compass, and (head)lamp with a full (and spare) battery.

To make orientation easier and faster, a mobile phone with preloaded, verified apps is also very useful. For tours in Slovenia, we recommend the maPZS app. Make sure that the battery of your phone is full and that you always have a Power Bank in your backpack.

Mobile phones have their advantages and disadvantages, which should be recognized, understood and considered. With that in mind, it’s easier to understand why these otherwise useful tools can often be more of a hindrance than a benefit if not used properly. Like with every other piece of equipment, it’s essential to learn how to use them effectively beforehand.

FIELD PROCEDURES

Choosing the right path is not always straightforward or “black and white”. Compromises must often be made between the complexity of navigation, the distance, and the physical effort required to follow the chosen path. Additionally, we must consider our experience, the terrain’s difficulty (steepness, potential obstacles, visibility, technical challenges), the weather, our technical equipment, etc. But our primary goal should always be to find the safest route to our destination, which might not be the shortest or the easiest.

We’ve already mentioned that it’s advisable to search for the target by narrowing down from a larger area to a smaller one. To illustrate: it would be hard to find a relatively small target (crossroads, hut, mountain pasture, etc.) from our current location, especially if we don’t know precisely where we are.

Walking by azimuth is suitable for covering short distances and navigating terrain without distinct features.

When covering longer distances, even a minimal error (which inevitably happens) can cause a significant deviation from the desired target. This will happen even faster when moving over rugged terrain (Karst terrain, steep slopes with gullies and ravines, etc.).

The easiest and often quickest way to reach our destination is by using the so-called catching and attacking points.

Photo: PZS/Matej Ogorevc

Instead of heading straight for our final destination, it’s better to look for a prominent object nearby that we can find much more easily. This could be a distinctive crossroads, the corner of a fence, a solitary large object, a confluence of streams, etc. This “object” is called the attacking point, as it is from there that we will “attack” our target/destination.

Unlike attacking points, warn us about moving away from our destination. It makes sense to set as many clear and easily recognizable catching points as possible to help us stay in the desired area. Good catching points are linear objects (roads), different bodies of water (streams, rivers), edges of a forest, pronounced terrain features, etc.

If we choose a road, a stream, and a rock barrier as the boundaries of our movement area, we’ll know that if we reach any of these objects, continuing in the same direction would mean moving away from the desired target/destination. A catching point can also be set beyond the target/destination – if we reach the edge of the forest on a mountain pasture while looking for a shelter in the middle of it, we’ll know we have gone too far and need to turn back.

EXAMPLE OF POOR VISIBILITY NAVIGATION

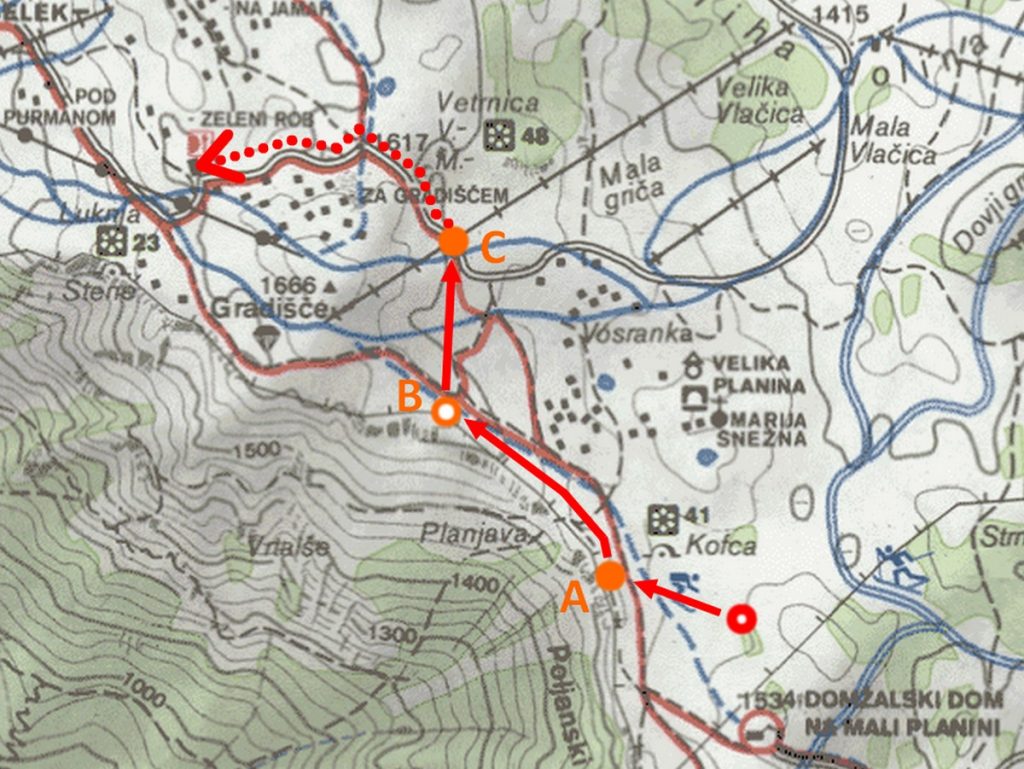

The image below shows an example of navigating in poor visibility from point = (red circle) to the Zeleni rob inn (dotted arrow):

- We carefully examine the surroundings on a suitable hiking map. In this case, the terrain is indistinct. We decide on a combination of walking by azimuth and the tactic of finding the path using attacking and catching points.

- On the map, we determine or estimate the direction of movement to a fence (point A – attacking point). We’ll reach it by following azimuth 280°. The fence is our attacking point.

- Once we reach the fence, we follow it northward. From the map, we determine that at the point where the fence turns west (point B – catching point), we need to turn north and continue walking to the road (point C – attacking point). We choose the ski lift as an additional point of reference or an additional attacking point in case we veer to the left.

- When we reach the road (point C), we follow it to the Zeleni rob inn. It is also helpful to keep in mind that the inn is the first large object to our right (north of the road).

NAVIGATION IN POOR VISIBILITY

If we get lost on unknown terrain due to poor visibility, carrying on is almost pointless. Aimlessly searching for a path and wandering in hard-to-navigate terrain only wastes energy and motivation. If we don’t want to wander in circles, it’s often better to wait for better conditions (if it’s reasonable to expect them). If we decide to keep going, we must be adept at various navigation techniques.

In reduced visibility, we should rely on the largest possible objects, such as roads, cart tracks, power lines, etc. These are sure to lead us somewhere and are easy to follow.

In winter, it often happens that we have to navigate based on terrain only. If conditions are even worse due to fog, navigating can be extremely challenging, as we can completely lose our sense of gradient. Such conditions result in so-called diffuse light, which has no specific direction of origin and doesn’t create shadows that allow the eyes to distinguish contrasts. In such conditions, identifying any terrain features becomes nearly impossible.